Report highlights community pushback stalling $64 billion in data center development nationwide

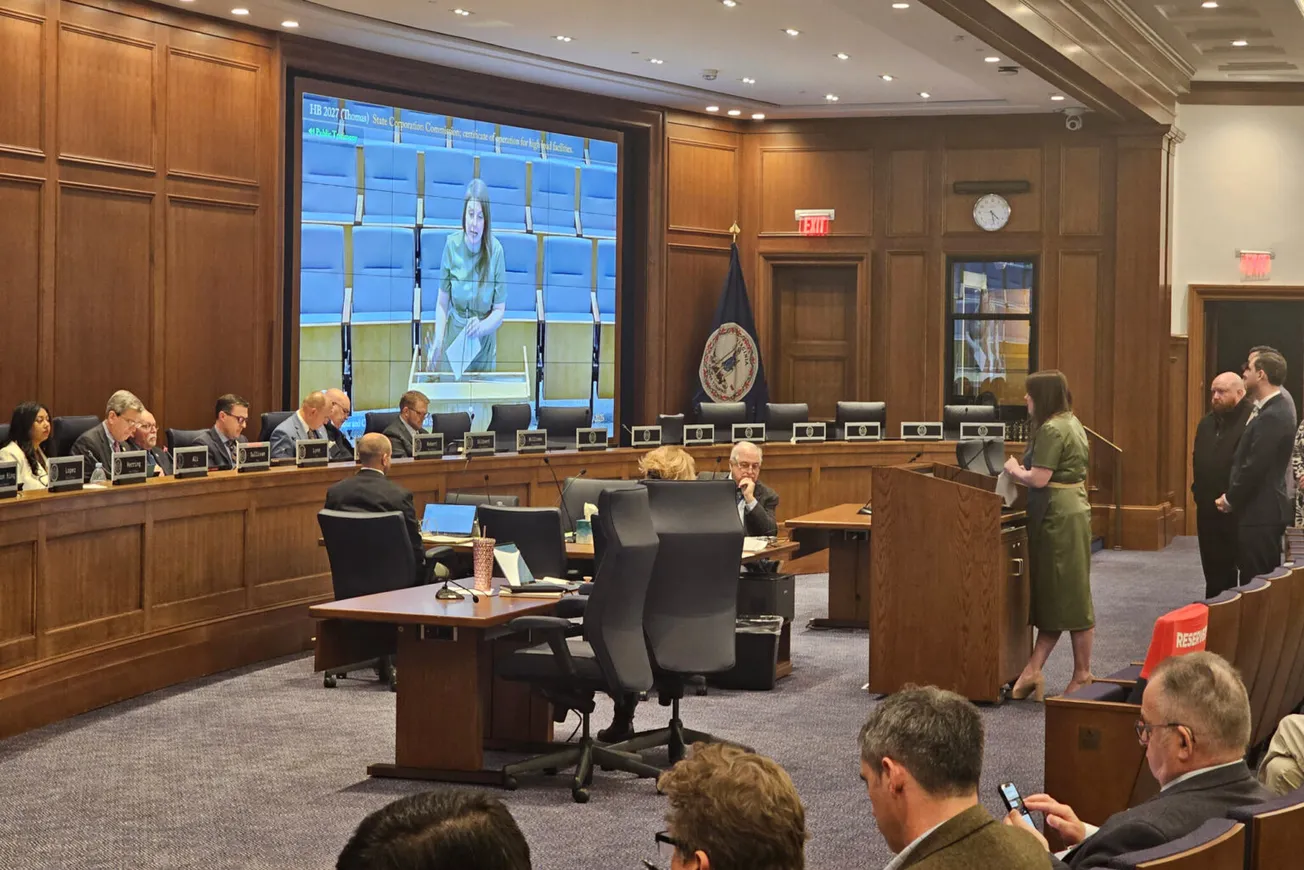

In Virginia, the globe’s largest concentration of data centers, and nationally, local opposition has coalesced into a powerful, bipartisan force

In Virginia, the globe’s largest concentration of data centers, and nationally, local opposition has coalesced into a powerful, bipartisan force