In newly Democratic Virginia, immigration enforcement becomes early test for Spanberger

The governor moves to curb state cooperation with ICE as advocates warn existing agreements remain and Republicans argue the change risks public safety

As federal immigration enforcement activity increases in Democratic-led states across the country, immigrant advocates and civil rights groups are warning that Virginia — which recently flipped full control of state government to Democrats — could be next.

Gov. Abigail Spanberger, sworn in earlier this month as Virginia’s 75th governor, has moved quickly to draw a line between state law enforcement and federal immigration enforcement, while acknowledging that much of the authority still rests outside her control.

Just hours after taking the oath of office on Jan. 17, Spanberger fulfilled a promise she made in an August interview with The Mercury, rescinding former Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s Executive Order 47.

The order had directed Virginia State Police and the Department of Corrections to enter into so-called 287(g) agreements with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, effectively deputizing state officers to assist with federal immigration enforcement and encouraging local cooperation with ICE to identify and remove noncitizens accused or convicted of crimes.

Spanberger’s executive action marked a sharp policy reversal after years of Republican leadership in Richmond and came as immigration enforcement has intensified in blue states under President Donald Trump’s renewed push for large-scale deportations.

“My executive order, repealing Executive Order 47, was an important first step in ensuring that we are not moving or reallocating state and local resources away from the first-responder duties, whether it is investigating crimes or being ready to support a community in need,” Spanberger said last week.

She emphasized the prior order “had created some real challenges.”

“Ultimately, I am looking to every step forward that we can take as a commonwealth to ensure that our communities are safe and protected,” Spanberger continued, adding that confusion around law enforcement authority has fueled fear in immigrant communities.

“Frankly, the fear and concern that we’ve seen in other places where people without any sort of designation — unannounced, wearing masks — are taking people off the streets, the level of fear that that’s created and the level of distrust and confusion is certainly not contributing to any strengthening of our communities, let alone keeping our communities safer.”

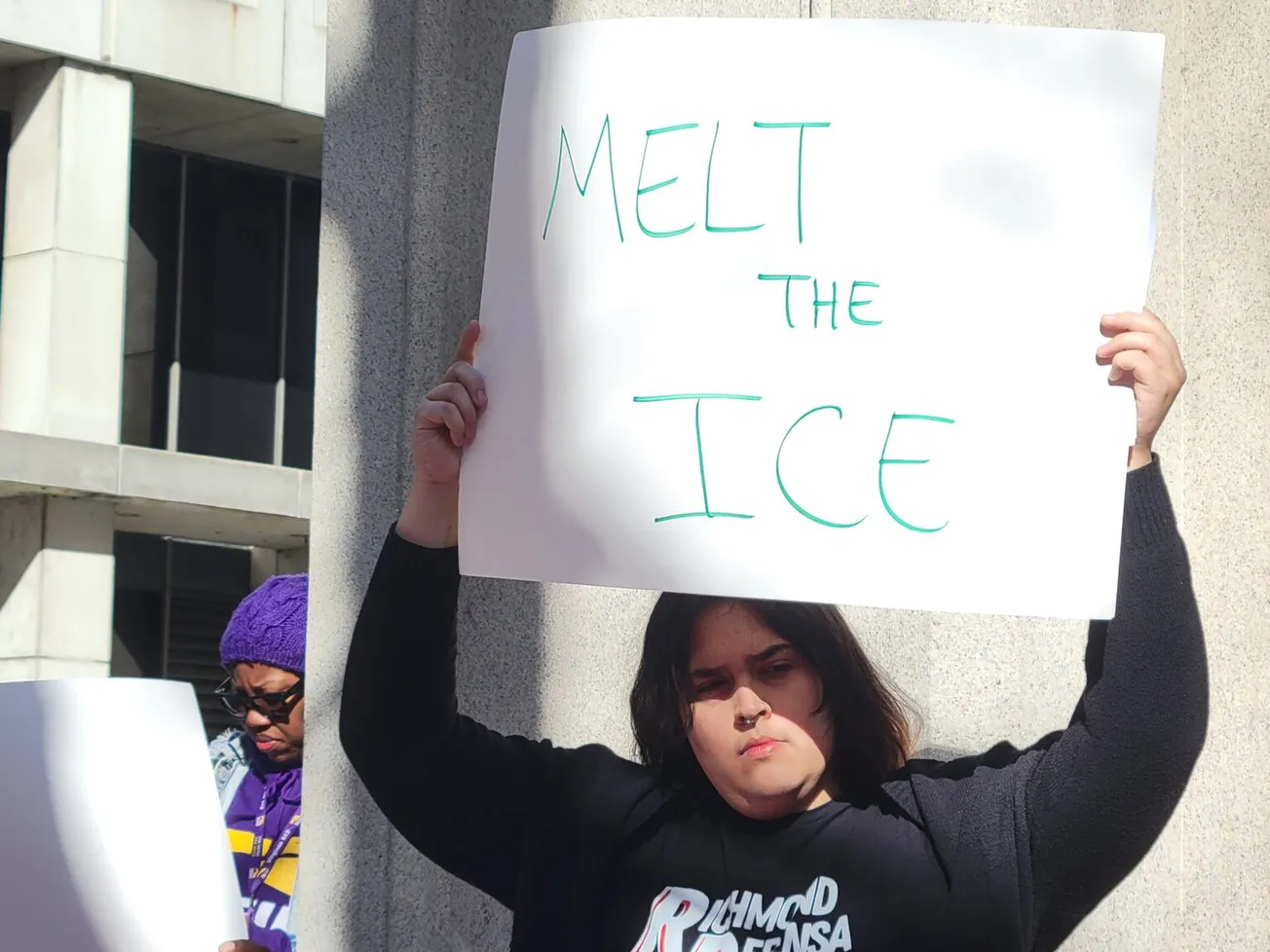

On Friday, members of Virginia’s Service Employees International Union chapters gathered outside a U.S. federal courthouse in Richmond to protest ICE enforcement, underscoring growing opposition from labor and immigrant advocates.

About 50 people attended the demonstration, where speakers criticized federal detention practices and read aloud the names of individuals who have been killed during ICE operations over the past year.

“We’re seeing the ICE escalate everywhere from from Minneapolis all the way here to Richmond,” said Violeta Vega, an SEIU member serving as an emcee for the gathering.

State action, limited reach

While Spanberger’s order ends the requirement that state agencies enter into 287(g) agreements, it does not terminate existing contracts between ICE, state and local governments, regional jails or sheriffs’ offices. Nor does it prohibit new agreements at the local level.

All state and local agreements “remain in force until terminated” by one or both parties, a new Legal Aid Justice Center analysis found. There has been no evidence to date that any existing contracts between ICE and state or local law enforcement have been ended as a result of the governor’s action.

The report details how dozens of agencies across Virginia — including state agencies and regional jails — have contracted with ICE to perform duties that may exceed their authority or conflict with state law and the Virginia Constitution.

The analysis further found that at least 223 state and local personnel have been nominated to participate in 287(g) agreements, including two school resource officers and a behavioral health advocate. One facility — the Riverside Regional Jail in Prince George County — receives more than half of its revenue from holding people for ICE.

“Those local law enforcement agencies with 287(g) agreements now have a massive financial incentive to abandon their mission to protect communities in favor of terrorizing immigrant populations,” said Alex Kornya, LAJC’s director of litigation.

“Contracts with ICE, often shrouded in secrecy, are not only a misuse of time and resources, but they also open these agencies up to significant liability, liability that Virginia taxpayers will ultimately pay.”

LAJC said many of the agreements were negotiated quietly, with agencies declining to provide information in response to public records requests — in some cases saying ICE instructed them not to respond.

According to ICE’s own website, there are currently at least 32 active 287(g) agreements in Virginia involving the state and local governments, and correctional facilities. Five are with state agencies, while the remainder involve local law enforcement.

ICE did not respond to a request for comment from The Mercury.

Fear, trust and public safety

Civil rights groups, including LAJC, say the impact of these agreements extends beyond immigration enforcement, undermining trust between immigrant communities and local law enforcement.

“Governor Spanberger’s action to rescind EO 47 on her first day was an important step, as these contracts do nothing to make people safer,” said Rohmah Javed, legal director of LAJC’s Immigrant Justice Program, adding that immigrant communities across the state are terrified.

“These agreements erode trust, making it much less likely immigrants will seek out needed services, report crimes witnessed or crimes they have experienced as victims, or participate in their communities,” Javed said. “But we need to see immediate action at both the state and local levels to officially end these abusive agreements.”

The ACLU of Virginia called the order a first step toward ensuring state law enforcement is not used for federal immigration enforcement, while cautioning that existing contracts and federal authority remain unchanged.

“Governor Spanberger’s executive order recognizes that blurring the line between Virginia law enforcement and federal immigration agents not only diverts Virginia resources away from public safety priorities, but erodes public trust by terrorizing communities and breaking apart families,” ACLU of Virginia Executive Director Mary Bauer said.

Republicans warn repeal of ICE order threatens public safety

Virginia GOP leaders, meanwhile, sharply criticized Spanberger’s decision, arguing that rescinding Youngkin’s order weakens cooperation with federal authorities and threatens public safety.

Youngkin himself told The Mercury in an interview earlier this month that rescinding his Executive Order 47 would be “a huge mistake,” calling it a necessary tool for combating violent crime and gang activity, particularly in Northern Virginia.

“That partnership has made Virginia safer. We arrested the number-three guy in MS-13; the number three guy in MS-13 was just living in Virginia that otherwise would have never been arrested,” Youngkin said.

In a post on X, formerly Twitter, former Attorney General Jason Miyares called Spanberger’s move “a disaster for the public safety” of the commonwealth. “Mark my words, there will be Virginians who will be robbed, raped and murdered as a result of this anti public safety executive order. No one should be surprised.”

House Minority Leader Terry Kilgore, R-Scott, also warned that ending mandated cooperation with ICE could lead to increased crime.

“Folks need to be able to walk their street at night without fear of being either shot or kidnapped or raped. It’s the wrong way to move with public safety in Virginia,” Kilgore said. “When Governor Youngkin had the agreement, we were able to catch all those MS-13 gang members up in Northern Virginia. If we’re not cooperating with ICE, folks are going to get harmed in Virginia.”

However, federal data show that immigrants without criminal records now make up the largest share of people held in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention, despite repeated assertions by some political leaders that enforcement is focused primarily on violent offenders.

According to ICE’s own figures, roughly 73% of those in detention as of late 2025 had no criminal conviction, and only a small fraction were held for violent offenses — many others had only minor or civil immigration offenses.

In Virginia, too, officials have not substantiated claims about the criminal histories of people rounded up by the state’s task force. Last summer, Youngkin claimed his administration had arrested more than 2,500 immigrants who were “violent criminals,” but Miyares at the time declined to provide evidence that those individuals were in fact violent offenders when pressed by The Mercury.

Local leaders respond

In Richmond, Mayor Danny Avula — the city’s first immigrant mayor — issued a statement addressing community concerns following reports of ICE activity in the region, including recent activity in Chesterfield County and Petersburg.

“I understand there is tremendous fear in the community right now,” Avula said. “Fear in completing everyday tasks, such as showing up for work, taking your children to school, or buying groceries, and I want you to know I hear you.”

Avula emphasized that Richmond does not coordinate with ICE on deportation activities and that the Richmond Police Department has not entered into a 287(g) agreement.

“Our officers are here to focus on their core mission: community policing, protecting all neighborhoods, and reducing crime,” Avula said, urging residents to call 911 if they need law enforcement assistance.

“I reject any approach that creates fear, confusion, or division,” he added. “Those tactics undermine public safety and erode trust, making our communities less safe, not more secure.”

Meanwhile, immigration enforcement concerns intensified last week after Hanover County officials confirmed receiving a letter from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security outlining plans to purchase and operate an ICE processing facility in a warehouse on Lakeridge Parkway.

County officials said the project was not initiated by Hanover and that the county has 30 days to respond. The Board of Supervisors had not convened to discuss the proposal as of Thursday and is expected to address the matter at its Jan. 28 meeting.

Virginia currently has two major long-term ICE detention centers — the Farmville Detention Center and the Caroline Detention Facility — along with regional jails that hold detainees under contract, including the Virginia Peninsula Regional Jail.

Advocacy groups say any expansion of processing or detention capacity could deepen fear in surrounding communities.

A broader political test

The debate over federal immigration enforcement underscores a broader challenge for Democratic governors in states where ICE activity remains governed largely by federal authority and locally negotiated contracts.

In Minnesota, Gov. Tim Walz publicly condemned a federal immigration operation in Minneapolis that sparked widespread protest after a federal agent fatally shot a 37-year old woman through her car window earlier this month. Following the killing, Walz demanded that the state must play a role in the investigation of the incident.

Coverage of the fallout has highlighted the limited tools Democratic governors have to rein in enforcement carried out independently by ICE or through local arrangements.

Similar tensions have surfaced in Illinois and Massachusetts, where Democratic governors back sanctuary-style policies but continue to face criticism when ICE makes arrests in jails and courthouses governed by local practices rather than state law.

In Illinois, confusion over the state’s TRUST Act has left sheriffs and the governor caught between immigrant advocates and federal officials. In Massachusetts, renewed attention to ICE courthouse arrests has put Gov. Maura Healey under pressure to respond to enforcement decisions she does not control.

Against that backdrop, Spanberger has emphasized that the stakes in Virginia are about trust — particularly whether immigration enforcement policies discourage people from calling police when they need help.

“Ultimately, how we will determine how Virginia proceeds is that — and I say this as someone who grew up in a law enforcement family and began my career in law enforcement — the idea that any community member would be afraid of calling police in a time of need, if there’s an emergency in their home, is a tragedy in and of itself,” Spanberger said.

Virginia Mercury reporter Charlotte Rene Woods contributed to this story.

Virginia Mercury is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Virginia Mercury maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Samantha Willis for questions: info@virginiamercury.com.