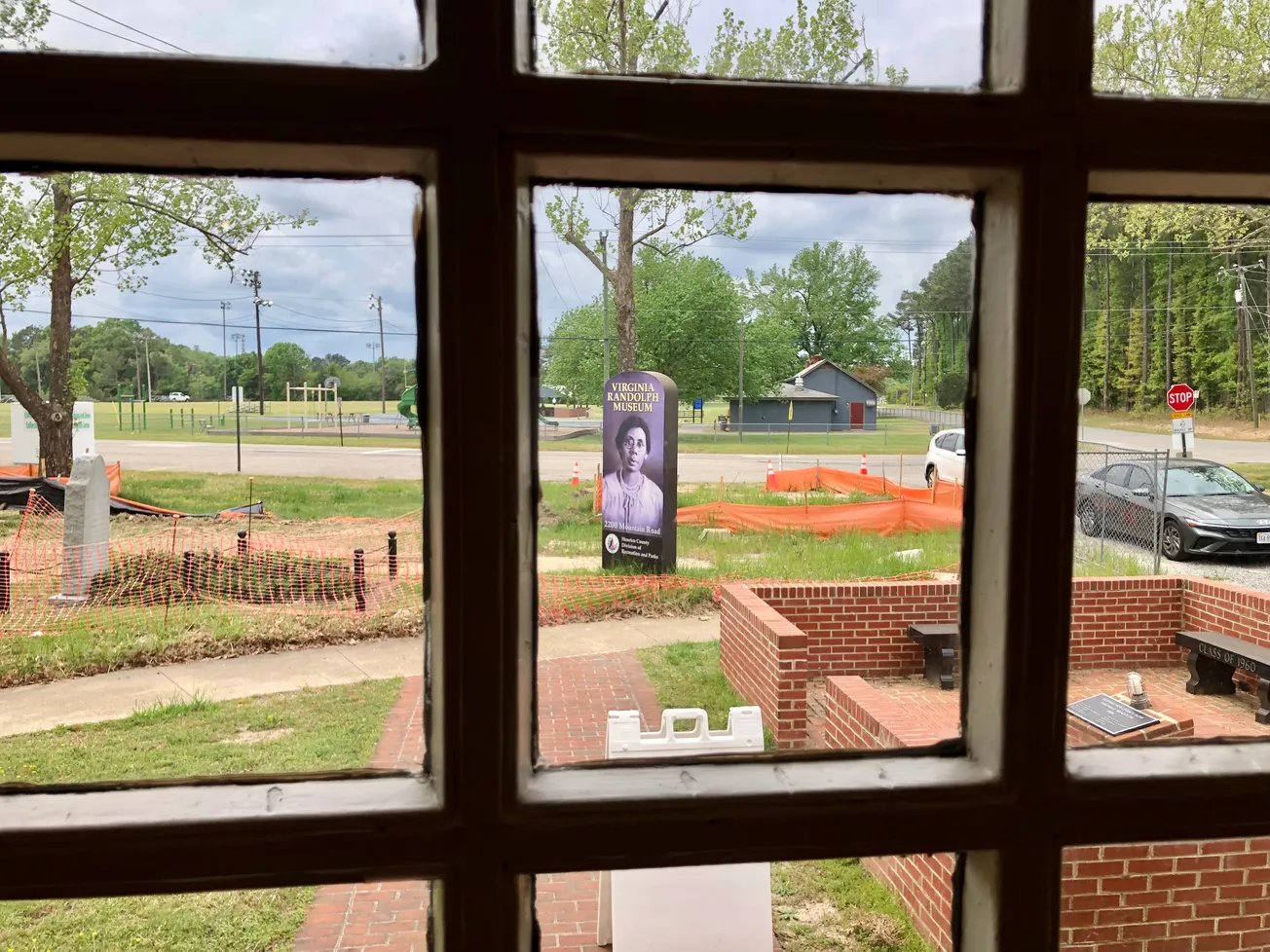

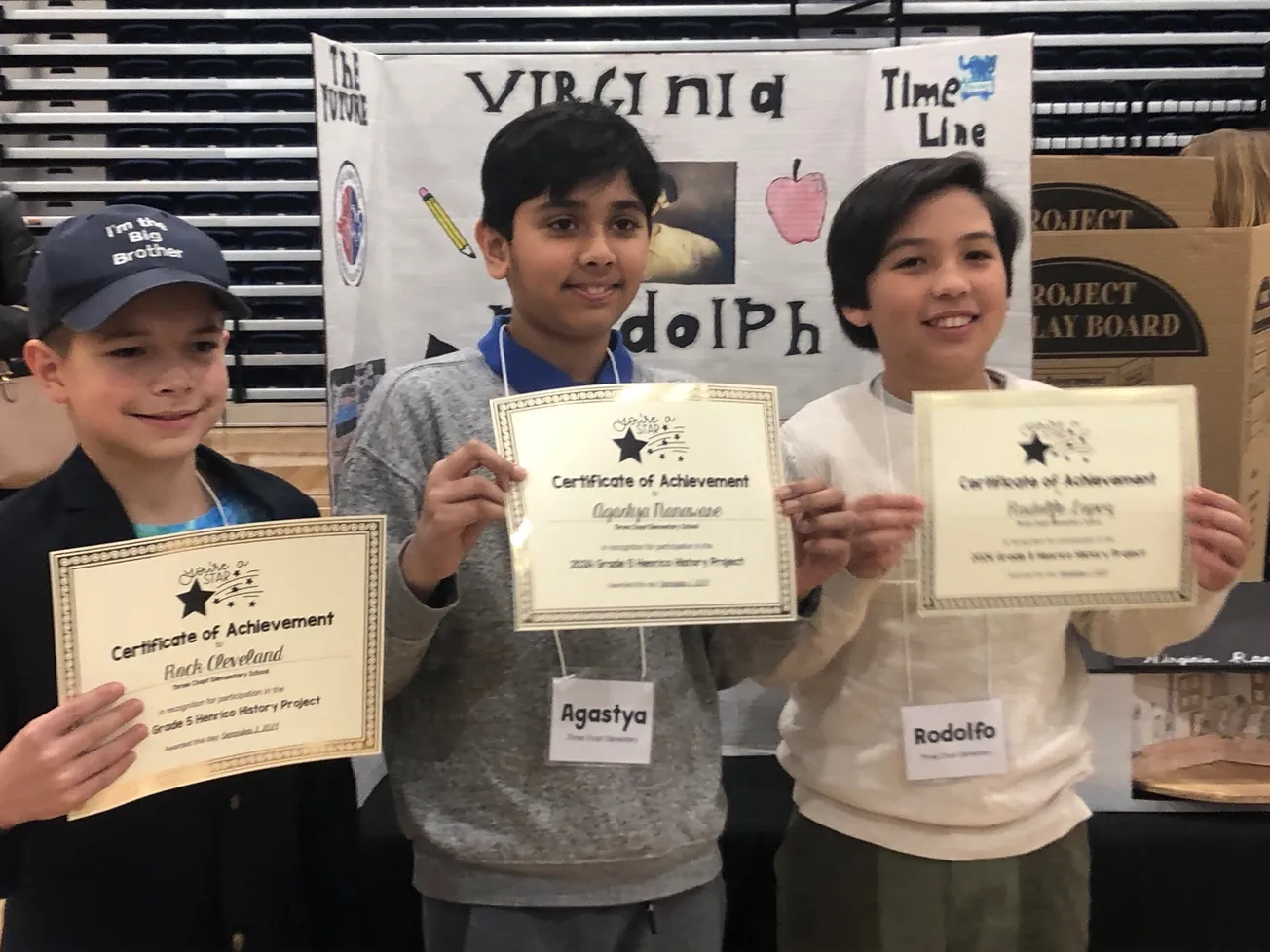

History — Virginia Randolph — Frank Thornton — The Small and the Mighty — Community — Glen Allen — Northern Henrico — Top News — Sharon McMahon

Author helps provide 'just desserts' for famed Henrico educator Randolph, who built unintentional legacy by doing 'the next needed thing'